Warrior Up – The “Other” Keystone XLs

Heiltsuk Nation chiefs speak at the United Against Enbridge rally of First Nations and allies during the first day of the federal court hearing on the multi-First Nation lawsuit, challenging the Canadian government’s approval of the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline across unceded territory. Credit: Courtesy Riki Ott.

Vancouver, BC. You’ve probably heard about THE Keystone XL pipeline, but have you heard about the other major pipelines just like it?

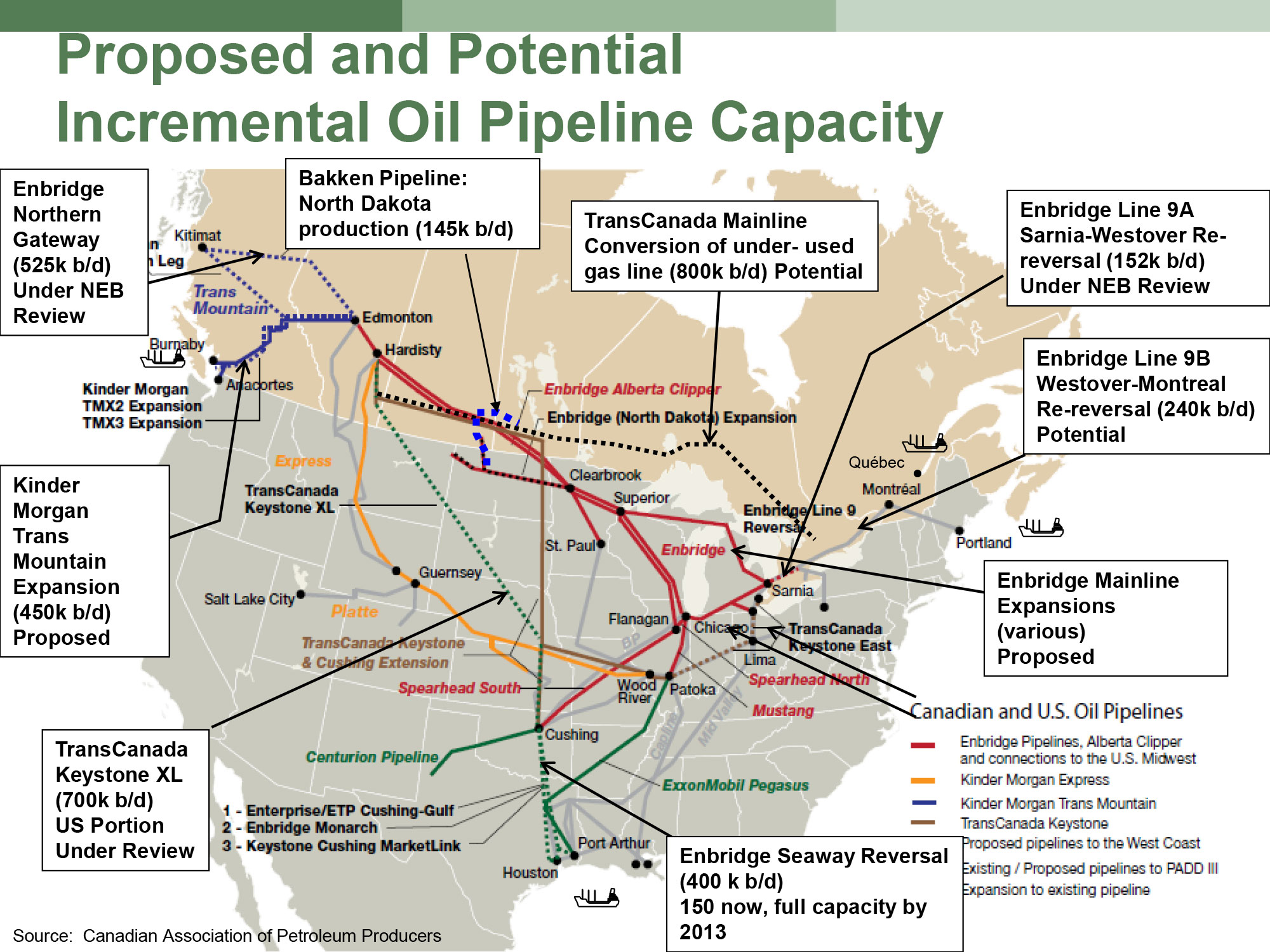

It’s a fact. Multiple pipelines link the land-locked Alberta tar sands to seaports in the United States and Canada for oil export. While the Keystone XL project has been used as a political football to distract serious solutions to the climate crisis, Alberta tar sands oil is already flowing to Port Arthur, Texas, via the original Trans Canada Keystone pipeline. The toxic bitumen runs through Steele City, Nebraska, and continues south via pipeline extensions to Cushing, Oklahoma, then Port Arthur, and now also via the Enbridge Seaway Reversal pipeline to Houston.

These are two legs of what I think of as the Alberta tar sands octopus. Two other large legs are designed to move oil west through Alberta and British Columbia. The Enbridge Northern Gateway – stalled in court – is proposed to terminate in Kitimat, BC, an inland seaport at the head of a deep water fjord. If built, tankers would carry oil through twisting, narrow Douglas Channel and the shallow, stormy seas of Hecate Straits. That feat may be possible only on a map – especially Enbridge’s maps, which are missing major landmasses to create an illusion of safety. Kinder Morgan is already running tar sands oil from Alberta to Vancouver, British Columbia, and is proposing to expand its Trans Mountain pipeline, tripling tanker traffic into shallow Burrard Inlet, and running another line to Anacortes, Washington.

The other four main pipelines are Enbridge Alberta Clipper and Kinder Morgan Express, already pumping tar sands oil from Alberta to Illinois. From Illinois, the oil flows south to Port Arthur via ExxonMobil Pegasus. Enbridge has proposed a series of flow reversals in existing pipelines to move oil eastward through Indiana, Illinois, Ontario, and Montreal to Portland, Maine, despite U.S. Dept. of Transportation concerns about impact of flow reversals on pipeline integrity.

ExxonMobil Pegasus, a reversed-flow pipeline, ruptured in Mayflower, Arkansas, in 2013. Oil flowed through neighborhoods and down streets, making people ill. Exxon has since demolished some contaminated homes and offered to buy 62 others in the Northwoods subdivision that was directly oiled, but not in adjacent or near neighborhoods where people also reported similar health symptoms. Credit: Emily Harris, MPH.

These are most of the major pipelines, but each year more pipeline projects are proposed or completed. Crude is shipped by railcar where pipeline projects are stalled. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers calls it, “incremental pipeline capacity.” Front-line communities call it “death by 1,000 cuts” or, in First Nations communities – genocide.

The fight needs to be reframed. It’s not just about THE Keystone XL. It’s about turning the Alberta tars sands into a “stranded asset” – where the oil stays in the ground. No pipelines. No railcars. No tankers. It’s about creative resistance and rethinking our energy future. All of us.

Twenty-one youth from across the United States filed a landmark constitutional climate change lawsuit against the federal government, as breach of public trust responsibilities to protect the climate for their generation. Meet the plaintiffs! photo: www.ourchildrenstrust.org

Former Hailsa chief Gerald Amos said it best at the May 2010 Gathering of Nations in Kitimat, BC. “This is about people. This is about the people having choices and having a say about what is going on in their territory,” he said.

It’s also about relationships, especially building relationships with others who live in different states or countries. It’s about sharing information, first-hand experiences, successes and failures with those who are dealing with similar issues and often having to face the same transnational oil corporations. It’s about celebrating our strength when we stand united. It’s about not giving up – system change happens incrementally, too.

For example, last week in Vancouver, British Columbia, Gerald Amos’ vision of a Gathering of Nations came full circle. During the 2010 Kitimat gathering, 35 First Nations with unceded territory along the proposed pipeline route created a new clan, committed to stopping the Northern Gateway project. This led to a formal Save the Fraser Declaration with over 70 First Nations, and then a multi-national federal lawsuit. During the federal court hearing that started last week, over 500 people with First Nations and allies celebrated in solidarity at the United Against Enbridge rally.

Riki Ott leads a workshop on opportunities for citizens to strengthen oil spill preparation and response planning to deal with the current threat in our cities. Residents use the information to engage local municipalities in preparing for oil spills as well as floods, fires, earthquakes, and other disasters.

Here’s where you come in. What about your backyard? What if you learned about the health risks, property damage and devaluation from “frackquakes,” land seizures from eminent domain, and other costly harms from oil activities in your own backyard, and then you took action to protect people and places you love? Not alone, but with others – like the people in stories shown here.

Direct actions like the Paddle in Seattle climate kayak-tivists help raise awareness and tip public favor against oil projects. Shell recently announced that it was withdrawing plans to drill in the Arctic. Credit: Backbone Campaign.

These people are working together, and their actions are making a difference. More actions will make a bigger difference. As Hereditary Chief Ian Campbell of the Squamish Nation said at the United Against Enbridge rally last week, “My grandmother told me: ‘It’s time to warrior up’.”

Riki Ott is director of ALERT. For her game-changing work on the front lines of oil spills and environmental disasters, the Make It Safe Coalition recognized Ott with the first Grace Lee Boggs Pillar Award for community activism in July 2015.