EPA’s New Rules on Oil Dispersants, Explained.

This background is intended to broaden the public understanding of the scope and significance of the 2023 updates to our nation’s emergency response plan – the “National Contingency Plan” (NCP) to protect our environment against hazardous waste releases, including oil spills. The rules were updated as a result of a 2020 lawsuit (Alert v. EPA).

When an oil spill occurs almost anywhere in the United States and its surrounding waters, local and state government’s response efforts follow the organizational structure in the National Contingency Plan (NCP) — a set of rules for oil spill prevention and response planning that is maintained by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under the Clean Water Act and the Oil Pollution Act.

The last substantial overhaul of the NCP was in 1994 in response to the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska. In the intervening nearly 30 years, the rules had become a tangled mess of jurisdictions that resulted in ill-informed decisions based on outdated science, misinformation, and lack of public involvement.

Disasters that occurred over 20 years apart, like the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, were governed by the same set of emergency response tactics — tactics that needlessly endangered people and wildlife, time and time again. In both incidents spill response led to catastrophic outcomes for response workers, residents, and wildlife.

The current revision focuses on Subpart J, which governs the use of biological and chemical products, including oil dispersants, that may be used during response to mitigate harm to the environment and “public health and welfare,” meaning to protect the water as the most appropriate and practical method to abate a health or safety hazard.

The National Contingency Plan, Explained

The 1972 Clean Water Act directed EPA to develop an NCP that included a schedule to identify “dispersants, chemicals, and other products” that may be used during oil spill response, the waters where they may be used; and what quantities can be used safely in such waters. “May” implies permission or something that is allowed, while “can” implies demonstrated ability to perform as described.

To address the first two permitted objectives, EPA developed a national screening protocol based on standardized laboratory tests using a “reference oil.” To be listed, products must pass both the efficacy test to determine how well the product performs (in lab conditions) and toxicity tests to help assess the relative risk of use compared to other products.

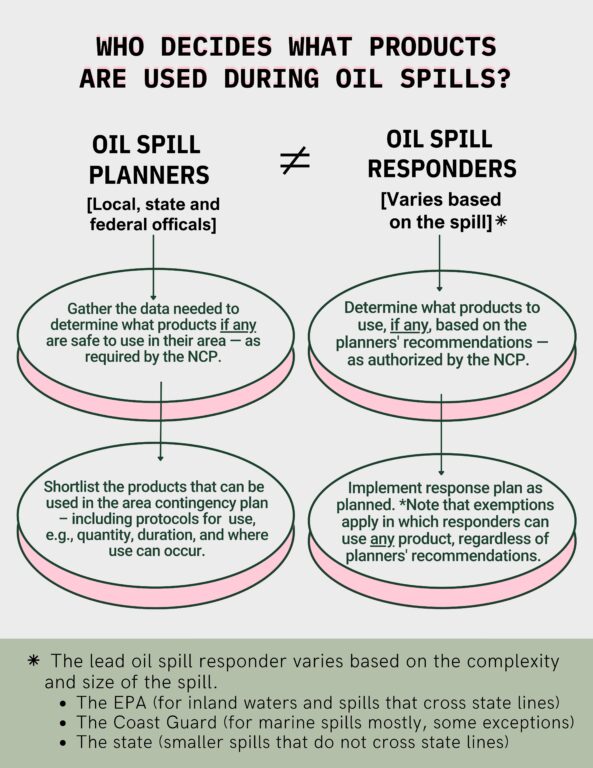

Significantly, EPA does not require the use of any products. Under the NCP, oil spill planners decide what products to use in contingency plans for their area or region, and oil spill responders decide what products to use during response. While planners may prescribe a subset of products chosen from EPA’s product schedule, responders may choose any product from EPA’s schedule.

This distinction can lead to decisions during response that further endanger people and the environment, especially in areas where planners have not prescribed specific products for use, based on ecosystem sensitivities and the unique characteristics of the environment.

To meet the third performance-based objective, Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, which established Area Committees, composed of regional, state, and local planners, and tasked them to work together to decide which products, if any, can be used safely in the specific ecosystems and areas under their jurisdiction. Yet this critical planning function languished due to lack of knowledge and funding for the testing and monitoring needed to meet this mandate.

Lacking quality information and local engagement to make informed decisions about ecosystem-specific use, area planning under the direction of mostly regional-level planners quickly defaulted to “preauthorization plans” that gave nearly carte blanche authority to the government entity leading an oil spill response. This means the EPA, U.S. Coast Guard, or lead state agency On-Scene Coordinator (OSC) could use any products on the national list during an oil spill without first determining where and how much of the products can be safely in the area.

How The Previous NCP Failed

One of the most striking examples of how the current NCP failed to protect people and wildlife was the widespread use of chemical dispersants during the BP oil spill.

Dispersants are petroleum-based products, which contain ingredients that are, by nature, hazardous to humans and wildlife. Therefore, state and regional planners recommend that dispersants are not used in coastal and shallow waters with insufficient volume to dilute the toxic effects. However, during response, the OSC routinely makes exceptions to this recommendation.

For example, the Coast Guard OSC during the BP Deepwater Horizon response authorized daily use of Corexit dispersants for nearly three months at the sea surface and subsea at depth – over 1.8 million gallons in total, not counting use in coastal waters that were stricken from daily reports.

While Corexit dispersants were listed on EPA’s product schedule, the prolonged use of significant quantities of product on the sea surface and at depth had not been authorized by the planners, meaning that no one knew if such “atypical use” could be done safely – or not. The experiment turned out badly. The unprecedented amount of products with known human health hazards and unknown environmental fates led to still ongoing long-term harm to people and to wildlife.

Recently revealed documents have shown how Louisiana state officials were pressured by BP to approve atypical use of dispersants, despite the officials’ concerns for fisheries and public safety. The Coast Guard OSC authorized atypical use of dispersants largely on BP’s assurances that such use would likely not further endanger wildlife or people, despite lack of hard data to support any of its claims.

The BP dispersant catastrophe demonstrates the danger when state and local governments lack the wherewithal, knowledge, and funding to deal with oil spills, even when policy is on their side — and how, in the absence of advance preparation and planning to address the concerns of state and local governments, industry interests can dominate during the panic of a spill.

The BP Deepwater Horizon double disaster is what finally precipitated changes to the rules governing use of dispersant and other oil-spill mitigating products.

What this new regulation does

With these new rules, the EPA closed many loopholes that have allowed toxic products to be used for decades. The regulations will go into effect in six months on December 11, 2023. They are a welcome improvement in critical respects. For example, the NCP will now provide, on a nationwide basis:

- Improved testing of the efficacy and toxicity of dispersants before they are listed on the NCP “product schedule” as permissible for use in oil response efforts.

- Public notification of when chemical and biological agents are deployed in emergency response situations.

- Significantly greater public disclosure of data relevant to dispersants’ chemical constituents, environmental fate, intended uses, and health and safety effects by prohibiting manufacturers from withholding this as “proprietary business information.”

- Removal of products based on misleading, inaccurate, outdated, or incorrect statements regarding product composition or use, including advertisements, technical literature, electronic media and more.

- Delegation of critical decision-making authority to local, state, and regional planners, allowing them to set even more stringent standards for the use of dispersants and other oil-mitigating products.

The new regulations compel the planners to determine whether products can be used safely, based on a wealth of required information like specific limits for quantities and duration of use, water depth, distance to shore, proximity to populated areas, and more. In previous spills, such information about products was not available.

But there is a catch. The rules opened the door to potential use of dispersants in significant quantities on the sea surface and at depth during very large oil spills – exactly what occurred during the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster with deadly consequences for response workers, impacted residents, and the environment.

By delegating authority to local, state, and regional planners to decide what products to use during spill response, the new rules attempt to provide tools and authority to states to better protect their wildlife and residents, i.e., the people who will live with the consequences of product use. But the rules mean nothing if the states don’t use them, if state efforts are not properly funded, or if regional planners don’t respect the states’ authority.

What happens after this rule goes into effect?

After the final rule date becomes effective on December 11, 2023, the EPA will allow all products currently on the national schedule to remain conditionally listed for another two years to be retested under the new protocols. All products that have not submitted the required information and been relisted on the schedule at the end of the conditional listing period on December 11, 2025, will be removed from the list.