Riki Ott commemorates the 30th anniversary of Exxon Valdez oil spill in solidarity with Heiltsuk First Nation lawsuit

Thirty years ago on March 24, 1989, the Exxon Valdez grounded on Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound, Alaska, spilling 11 million gallons of crude oil into the ocean. This set off a chain of events that still informs decisions and actions today by government, courts, the oil industry—and by people who don’t want the next “Big One” to be in their backyard.

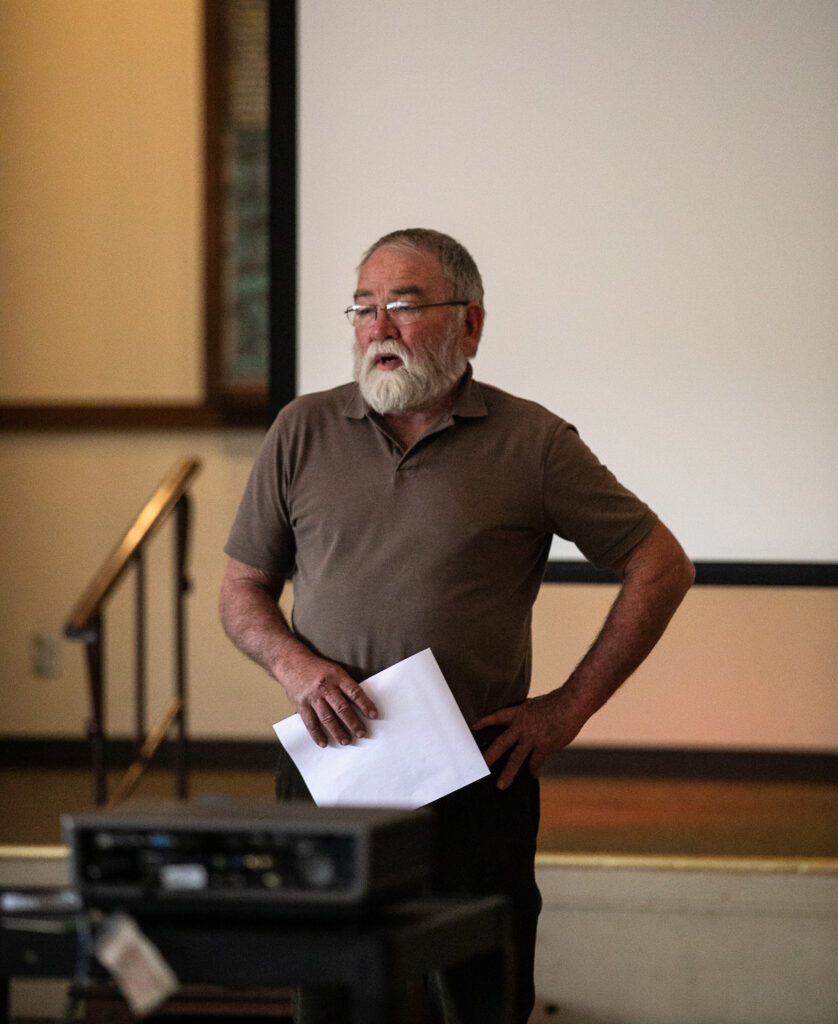

On the Exxon Valdez memorial this year, I spoke at a gathering of just such people at the Ballard Elks Lodge in Seattle on the shore of the Salish Sea. Organizers included Friends of the Earth, RAVEN Trust on behalf of the Heiltsuk Nation, and Washington Environmental Council.

Oil spills, like the environmental oil disaster that happened last month in the Solomon Islands marine reserve, continue around the world.

An oil spill struck the The Heiltsuk Nation on October 13, 2016.

The Nathan E. Stewart, a tug-barge combo, ran aground when the watchman fell asleep causing an oil spill in Heiltsuk marine waters. Over 110,000 liters of diesel fuel and other pollutants spilled into Gale Pass, an important Heiltsuk food harvesting and cultural site.

The Heiltsuk Nation are now taking legal action suing the oil shipping company and Canada to protect their lands.

The presentation and demonstration were to learn lessons from the Exxon Valdez disaster to inform present actions to increase safety measures for oil transportation through the Salish Sea and spill response.

Ken Workman opened and blessed the event. Ken is a member of the Duwamish Tribe. He is a direct descendent of Chief Sealth, the man for whom Seattle is named.

As one of the Exxon Valdez oil spill survivors and former Alaska fisherma’am at the event, I spoke about how we are now back to the institutionalized government and industry complacency that contributed to the 1989 spill. I described the new scientific understanding that oil causes long-term harm to people and wildlife at levels 1,000 times lower than levels previously thought to be safe that emerged post Exxon Valdez, and the new studies showing that oil and dispersants combined are far more deadly than oil alone to people and wildlife. I also alerted people to upcoming actions to update EPA’s National Contingency Plan for oil and chemical spills.

Tom Copeland, a commercial fisher scooped up oil in Prince William Sound in five-gallon buckets when Exxon’s initial spill response proved utterly inadequate. Tom addressed the inadequacy of oil spill prevention and preparation in Washington State compared to post-spill Prince William Sound.

Verner Wilson III is the Senior Oceans Campaigner of Friend of the Earth’s Oceans and Vessels Program and a member of the Curyung Tribe in Dillingham, Alaska. Verner focuses on protecting the marine environment from shipping pollution and disturbance in the Pacific Northwest and Arctic. He spoke about the intense emotional and social trauma of the Exxon Valdez, even though he was only three at the time—and how it affected fishing communities and people across Alaska.

Fred Fellemen, a Port of Seattle Commissioner, talked about the articulated tug barges that carry as much or more oil than was spilled by the Exxon Valdez and yet are not required to have tug escorts like oil tankers. ATBs need only half or less of the crew required by tankers and save shippers money—until the inevitable spill. The industry calls ATBs “rule-breakers” and are indifferent to the heightened risk they present to our ocean and communities.

Anna Doty with Washington Environmental Council gave an update on the status of legislation to require ATBs and oil barges to retain tug escorts while navigating Rosario Strait in the San Juan Islands.

Ann Simeon spoke on behalf of the Heiltsuk First Nation in British Columbia. The Heiltsuk are screening their film, Raven People Rising, to raise funds for their lawsuit against the Canadian government to demand sovereignty over marine waters, subtidal lands, and intertidal lands to have a say in what ships are allowed to navigate their waters.

It was a beautiful event that wove the past, present, and future together—intergenerational intent, informational, and inspiring with much possibility for actions.

Afterwards, we laid a 100-foot long piece of black fabric on the beach to remind legislators what our shores might look like if we don’t ALL act to protect Washington’s waters from oil spills. We picked up the cloth to demonstrate that we want oil spills prevented or picked up in the advent of a spill.