I had this overwhelming feeling that I was dying.

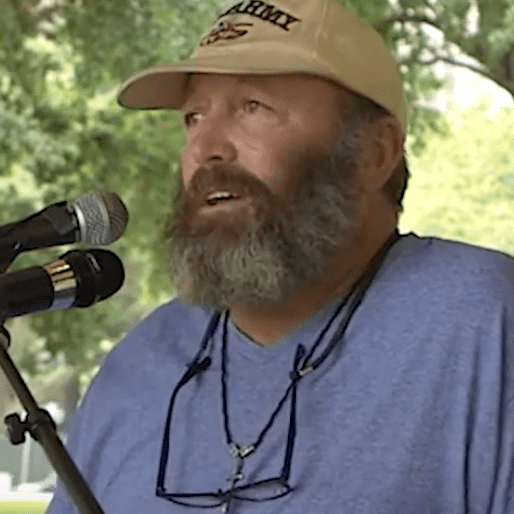

Frank M. Howell, contracted boat captain during the 2010 BP oil response

Frank M. Howell began working as a boat captain on the BP oil spill in May 2010. During the long and hot days working on the spill, Frank said the small open boats meant that the crew was often getting sprayed with oil-and-dispersant-contaminated water and mist.

Just a few months later, Frank developed a painful chronic cough. Then the health issues quickly escalated.

“Several times I’d wake up on the floor in a puddle of blood,” he said. “I had this overwhelming feeling that I was dying.”

His regular doctors were unable to diagnose Frank, so he went to see a neurologist. There, he tested positive for toxic exposure.

Today, Frank still has a chronic cough, blood pressure swings and chemical intolerances to the smells of bleach, gasoline and diesel. He also gets chronic headaches, and his vision problems persist. He is currently suing British Petroleum for dismissing his medical bill claims.

During the training, they told us we would not probably come into contact with chemicals. If I knew what I know now, I would not have taken the job.

Terry Odom, contracted safety officer during the 2010 BP oil response

Terry Odom was contracted by BP as a safety officer during the 2010 oil spill response.

“Health risks were downplayed during the training,” said Odom. “Contract workers were not trained to recognize symptoms of oil-chemical exposures. Most, including me, were not even screened for pre-existing illnesses."

Within weeks, she started showing symptoms of extreme chemical exposure.

“Every part of me that was exposed just broke out, it was like someone dumped me in a vat of fire ants.” She said.

Odom was recently diagnosed with asthma, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension. She did not have any of these conditions before her oil spill work in Pensacola, Florida. Odom has a current lawsuit against BP for her illnesses, which she believes come from her oil spill exposures.

Frank Stuart ran a company of oil spill response workers in Louisiana, which was one of the first contracted by BP to work on the spill. In February 2018, he fell suddenly ill, and doctors had no idea what was causing his symptoms.

Stuart died just three months later of acute myeloid leukemia, a rare blood cancer linked with exposure to oil spills, just one day before the eighth memorial of the BP oil disaster.

BP never told us or the doctors that the oil spill exposures were potentially lethal or could cause a problem eight years later.

Sheree Kerner, Frank Stuart's wife

Greg Brown was working on the BP response when his boots filled up with water contaminated with oil and dispersants. Within days, his legs became infected. Doctors couldn't identify any bacteria that could be causing the infection, so they eventually determined that Greg had suffered a chemical burn from the inside out.

“It got to hurting so bad that I wanted to go ahead and cut [my legs] off," he said.

Within two weeks, his wife Jamie, who had never even gone near the spill, passed out in her bathroom alone. To this day, they both suffer from chronic illnesses.

They treated him as a soldier [contaminated] with Agent Orange.

Jamie Brown, wife of BP response worker Greg Brown

Even though Greg's wife Jamie Brown never went near the spill, she had large blisters on her hands from what doctors at the time told her was contact dermatitis. She wasn't doing anything differently, except for that she had been washing her husband's clothes when he came back from working on the spill.

Later, doctors discovered she had blood clots in her lungs. To this day, she needs her blood tested every two to four weeks, and she is on blood thinning medication for life. She says she still gets reactions if she touches her husband's sweat.

“If I touch the sweat on his head or his clothes, I get rashes on my hands again. If I sleep on his pillows, I get rashes on my face. So something’s still coming out of him that affects me,” she said.

Never compare resilience from a storm with an oil disaster. I can rebuild after a storm, but life after toxins is an everyday life sentence for the rest of my life.

Lori Bosarge, Gulf Resident

Lori Bosarge lived in Coden, Alabama, during the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill. During the months of disaster response, Lori witnessed boats spraying Corexit oil dispersants in Portsville Bay, a quarter-mile from her home. When the prevailing breezes blew from the Gulf Coast, the sweet citronella smell of dispersants penetrated her home, despite all the closed windows and doors.

On August 21, 2010, Lori was directly sprayed by dispersant Corexit 9527A at a nearby Alabama marina. Her skin turned sunburn red moments after exposure. But that was only the beginning of Lori’s battle with Corexit’s “awfulness.” Contact with Corexit dispersant completely altered Lori’s health and quality of life.

In the years since, Lori has developed sensitivity to scents (chemicals), light, and noise that unnerve her. She had to abandon her trade. The “regular smell” and usage of everyday items, such as perfumes, Lysol, candles and Dial dish soap cause her throat to “close up like an asthma attack” so she avoids their use. Her skin is armored like “reptile skin.” Prior to her contact with Corexit 9527A, she had no allergies or rashes. She has been unsuccessful at getting disability and continues to amass medical bills from the day “all this awfulness” began over fourteen years ago—by an encounter with Corexit dispersant.