Since 1989, we have been fighting for oil spill policy reform and mobilizing community voices in areas impacted by oil-gas activities across the country.

We have traveled the United States and internationally training and mobilizing front line communities with accessible science, health education and legal action tools to better prepare communities for oil spill response and protect from toxic exposure during oil-chemical disasters.

Our work is informed by the model created by our Founder, Riki Ott, after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska.

Here's our impact story.

PRE-ALERT: Gaining Experience and Allies

1989 - 2010: Activating and Community Response

Credit: Kathy Halgren, 2010. Frustrated by Exxon’s slow and inadequate oil spill response, Captain Tom Copeland and his crew collected surface oil from bays where the floating oil was three feet thick. They used herring pumps to suck up the oil into totes and then transferred the oil into buckets. Oil coated the cliffs (in the background) to the high tide line.

1989

The night before the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska, Ott warned the Valdez Chamber of Commerce, “It’s not a matter of if, but when, the big oil spill occurs…” She advocated public involvement in better prevention and response measures. A little later that evening, the ill-fated tanker fully loaded with 53 million gallons of crude oil left the Valdez terminal. The next day, entire communities of people activated to respond to the nation’s largest maritime oil spill (11–33 million gallons). Some stayed activated. Ott was one.

Credit: Kathy Halgren, 2010. A deck load of oil buckets off-gassing. The “Oil Bounty” was delivered to Exxon in Valdez.

1990 - 1992

Ott (as board member of Cordova District Fishermen United and United Fishermen of Alaska) led a coalition of commercial fishing and environmental organizations to successfully advocate passage in Alaska of the strongest oil spill prevention and response laws in the United States at the time. Her work on behalf of the fishing community also contributed to passage of the U.S. Oil Pollution Act of 1990. This law established local and state involvement in developing Area Contingency (C-) Plans for oil spill prevention and response and for double-hulled tankers, among other things.

Credit: Tony Bickert, 1993. One hundred commercial fishing boats with families onboard blockaded Valdez Narrows and held up oil tanker traffic to bring national attention to the ailing Prince William Sound ecosystem—site of the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

1993

Ott helped organize what became the Fishermen’s Blockade of Valdez Narrows to focus national attention on the collapse of the Prince William Sound ecosystem. The blockade disbanded after three days on a pledge from President Clinton to conduct “comprehensive ecosystem studies” to determine the cause of the collapse four years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Communities suspected the oil spill.

Credit: David Janka 2003. Disk Island, Prince William Sound. Comprehensive ecosystem studies included beach surveys to track the degradation of oil lying buried beneath the rocks. It degraded slowly and continued to impact generations of young pink salmon and herring that used the protected bays as nurseries to develop and grow, and the young sea otters and birds that ate the contaminated shellfish.

1994 - 1998

Ott founded what became the first sustainable community project in Alaska, the Copper River Watershed Project, to provide options for rebuilding the local fisheries dependent economy in ways that also protected salmon habitat. Timely publication of Ott’s first book, Alaska’s Copper River Delta, helped shift attitudes towards sustainability. Over time, the Watershed Project helped restore the community’s sense of wellbeing that was shattered after the oil spill. In 2023, it became the first U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s Bipartisan-Infrastructure Law-funded fish passage project to break ground.

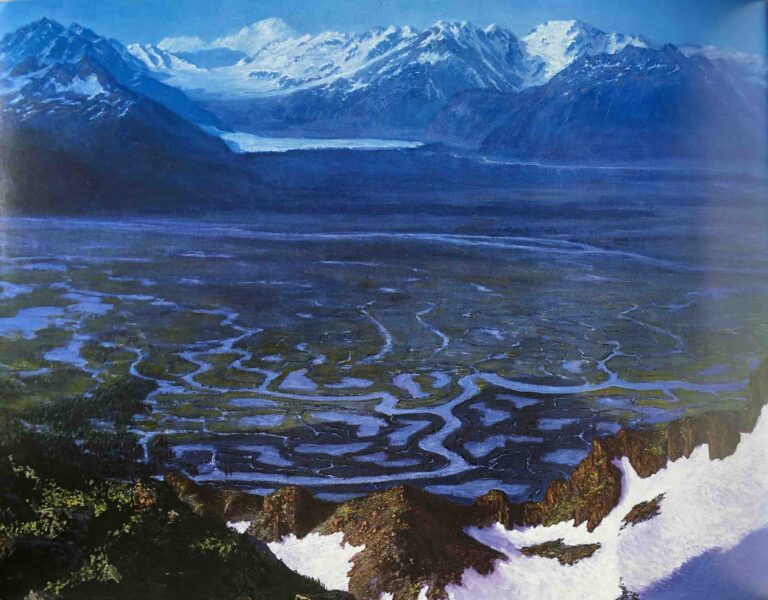

Credit: Artist for Nature Foundation 1998. Painting by David Rosenthal of the Copper River Delta, the largest contiguous delta on the U.S. Pacific Coast and a critical stop-over for migratory waterfowl and shorebirds.

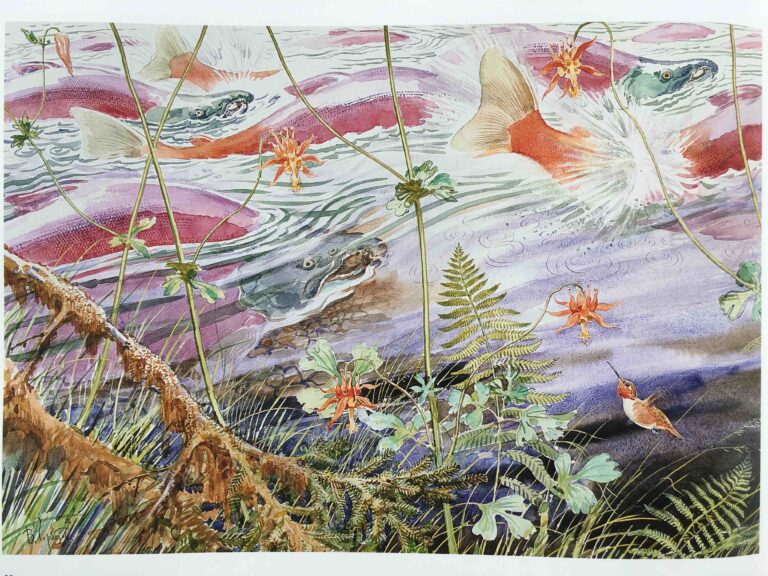

Credit: Artist for Nature Foundation, 1998. “Upstream and down, salmon are common ground” (Copper River Watershed Project). Wild-caught Copper River sockeye salmon were niche-marketed to support fishermen and the community after the oil spill closed fisheries in Prince William Sound. Today, these salmon are considered a premium fish by markets, restaurants, and chefs. Painting by Vadim Gorbatov. These fish are headed upstream 200-300 miles to spawn.

Ott Shares Lessons Learned From Exxon Valdez Oil Spill

2001

Ott (as co-founder of the Alaska Forum for Environmental Responsibility, AFER) convened the lead scientists for the ecosystem studies to synthesize their findings. The comprehensive ecosystem studies linked the Exxon Valdez oil spill with long-term ecosystem harm. The studies created a new understanding that oil was much more toxic to wildlife than previously thought, and they shifted ecosystem monitoring from looking at recovery of individual species to examining recovery of spill-affected communities and ecosystems.

Credit: Milo Burcham 2008. Populations of harbor seals and harlequin ducks were among the many species that slowly recovered after the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

Credit: Milo Burcham 2008. Populations of harbor seals and harlequin ducks were among the many species that slowly recovered after the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

2002

Ott (as AFER) and Alaska Community Action on Toxics conducted a pilot study to investigate the oil spill’s long-term impact on worker health.

2003

This led to a Yale University master’s thesis that found Exxon Valdez oil spill response workers reported a higher prevalence of respiratory and neurological conditions than non-workers thirteen years after initial exposure. This was the first study to find long-term harm to human health from an oil spill.

Courtesy: Michelle O’Leary, 1989. Beach workers used high pressure hot- or cold-water washes during the Exxon Valdez oil spill response to move oil off beaches into the ocean where skimmers could pick it up. However, workers were at risk from breathing aerosolized oil mist and particles while the oil from the beach mixed with sediment and sunk.

2004

Ott’s second book, Sound Truth and Corporate Myths focused on the oil spill’s impact on human health and wildlife. Making science accessible contributed to the first effort to reopen a natural resource damage assessment settlement for unanticipated harm—and it inspired other countries to investigate long-term health impacts from oil spills.

2008

Sound Truth was translated into Korean following the Hebei Spirit oil spill in South Korea. Ott was invited to present at the first international scientific symposium in Taean, South Korea, on long-term human health impacts of oil spills along with Korean researchers and Spanish researchers who studied impacts from the Prestige oil spill (2002).

Courtesy: Riki Ott, 2017. Volunteers push oil ashore for collection during the Hebei Spirit oil spill response in Taean, South Korea in 2007.

Ott Lays the Foundation to Address the Democracy Crisis

Credit: David Janka, 2008. Headlines the day after the U.S Supreme Court decision on the private damages class action lawsuit announced it’s over. The court reduced the jury-decided compensatory award to 10 cents on the dollar. Captain Janka dug a shallow pit on Smith Island to reveal the 19-year-old crude oil underneath the surface. For the ecosystem and fishermen, it was far from over.

2008

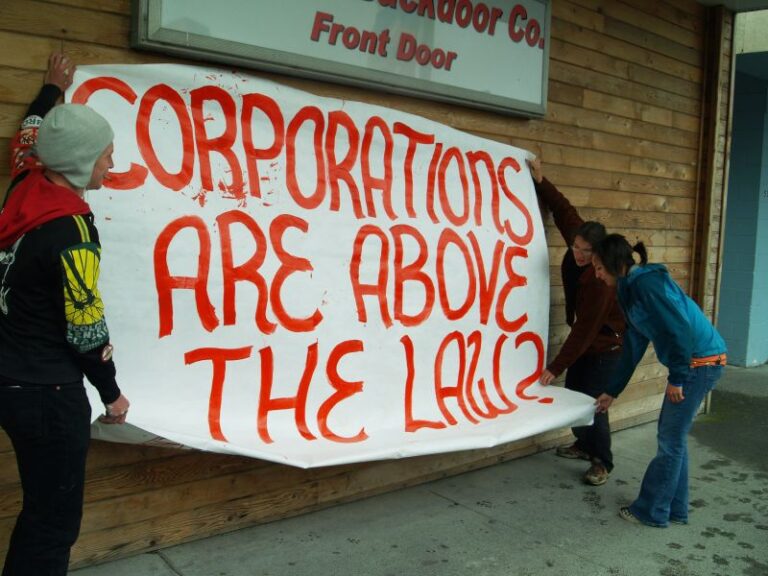

Ott’s third book, Not One Drop, described the lingering social, economic, environmental, and judicial fallout of Exxon Valdez oil spill. She concluded such harm could only be prevented by reforming our broken democracy, in which corporate power currently holds sway over human rights. Her 9-month book tour during the economic meltdown convinced her people across the nation were fed up with corporate rule.

Credit: Linden O’Toole, 2008.

2009

Ott co-founded Ultimate Civics to engage youth in activating democracy. Anticipating that the Supreme Court ruling in Citizens’ United would diminish people’s power, Ultimate Civics then co-founded MoveToAmend to amend the U.S. Constitution and establish that only human persons have human rights, and that money is not a protected First Amendment right.

Courtesy: Riki Ott, 2016. Sunnyside Environmental School students packed two courthouse rooms during the first hearing of Youth v. Gov and expressed their solidarity during the press conference after the hearing.

Courtesy: Riki Ott. Teaching constitutional rights to middle school students at Sunnyside Environmental School in Eugene, Oregon.

2010

National polls after the Citizens United decision show 85% of Americans across political divides disagreed with the Supreme Court’s decision. MoveToAmend has steadily gained support for its We the People’s Amendment.

Courtesy: MoveToAmend 2013. Rally in San Diego, California.

BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

Credit: USCG CPO 1C John Masson 2010. Controlled burn transferred oil into air and contaminated coastal and near coastal communities.

2010

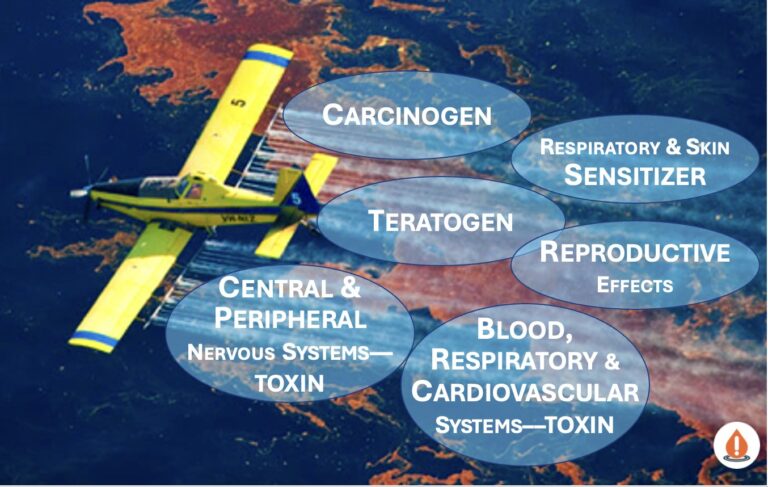

The BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill (210 million gallons) and massive use of Corexit dispersants (2 million gallons) became the nation’s largest oil spill. Ott embedded in Gulf Coast communities for the first year to coach people on what to anticipate in terms of personal, socio-economic, and environmental impacts, the claims process, and how to collect evidence of harm. A joint EPA and U.S. Dept. of Justice team used the citizens’ evidence for the federal civil lawsuit against BP, and it contributed to listing specified acute and chronic medical “conditions” for compensation under the BP class action medical benefits settlement—the first one to acknowledge human health impacts from oil spills.

Courtesy: Riki Ott 2013.

Courtesy: Riki Ott 2013.

2011 - 2017

Ott/ALERT toured the Gulf Coast states thirteen more times from 2011 to 2017, hosting workshops, giving trainings, and helping communities organize as people continued to experience long-term impacts from their initial oil-chemical exposures and/or to daily emissions from oil-chemical facilities. This work led to a citizens’ petition to EPA to update the rules governing dispersant use (2012), a rulemaking process, and, ultimately eleven years later, new rules (2023) to eliminate the more toxic products (see ALERT Impact).

Courtesy: Riki Ott, 2017. ALERT workshop training in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Tar Sands Oil Pipeline Tours

2010

Ott’s oral report from the BP Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in 2010, delivered in person in Kitimat (British Columbia, Canada), contributed to creation of the Solidarity Clan of First Nations with unceded territories in southern British Columbia to block the proposed Enbridge Northern Gateway tar sands pipeline.

2012

Ott’s “Think Tanker Tour” in southern coastal British Columbia, organized by Haida and Haisla First Nations and other allies, contributed to election of more progressive province leadership.

Courtesy: Riki Ott, Solidarity on Haida Gwai’i: No pipeline, no tankers, no problem.

2011

Michigan communities harmed by the 2010 Enbridge pipeline spill into the Kalamazoo River organized Ott’s first “Tar Sands Oil Spill Tour” to share and compare experiences from tar sands-diluent (dilbit) exposures with conventional oil-dispersant exposures.

Courtesy: Riki Ott 2013. Ott set up the Timeline of Rights & Privileges in Paris, Texas, as part of her “What the Frack Tour,” organized by Texas Tar Sands Blockaders and others.

Courtesy: Riki Ott 2013. Ott set up the Timeline of Rights & Privileges in Paris, Texas, as part of her “What the Frack Tour,” organized by Texas Tar Sands Blockaders and others.

Courtesy: EPA, 2013. Ott crossed the Red River into Arkansas, where EPA was responding to the ExxonMobil Pegasus Pipeline tar sands oil spill in Mayflower, Arkansas. Residents described haunting chemical illnesses six years later.

Courtesy: EPA, 2013. Ott crossed the Red River into Arkansas, where EPA was responding to the ExxonMobil Pegasus Pipeline tar sands oil spill in Mayflower, Arkansas. Residents described haunting chemical illnesses six years later.

Courtesy: Riki Ott, 2013. A workshop in Dallas, Texas, was part of the “What the Frack Tour” that resulted in a comprehensive grassroots strategic plan for oil transition and the first Texas town to ban fracking within city limits, which resulted in a protracted political battle.

2014

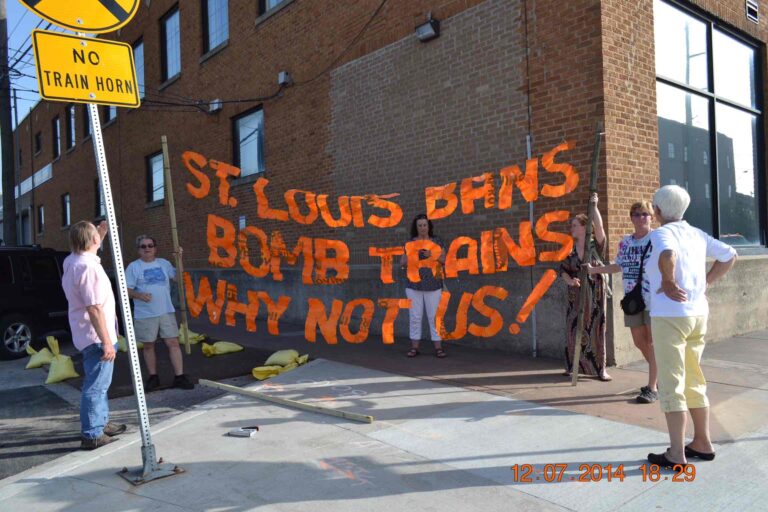

Ott’s “Extreme Oil, Extreme Consequences Tour” up the Mississippi River drew links between human experiences of chemical illness and industrial fracking operations in or near communities—and corporate rule. This led to a citizens’ supplemental petition to EPA to address response measures for tar sands and fracking oil, which EPA did not do, and to include stronger provisions for local and state decision-making and protecting worker and public health, which EPA did (see ALERT Impact).

Dakota Ban Bomb Trains.

2015

Ott’s oral expert testimony before the Canadian National Energy Board on behalf of the United Haida Nation in 2015 also contributed to allies’ successful efforts. The Northern Gateway pipeline project was cancelled in November 2016 after a Canadian Court of Appeal ruled that consultation with First Nations was inadequate.

Courtesy: Riki Ott, 2015. Ott prepared technical comments for Canadian allies on Canada’s proposed rulemaking to allow Corexit dispersants. Despite public opposition, the Canadian government authorized their use.

Courtesy: Riki Ott, 2016. First Nations rally in opposition to the Northern Gateway Pipeline Project at courthouse in Vancouver, British Columbia.

ALERT'S IMPACT: CREATING CHANGE

2014

Ott founded The ALERT Project in August through Earth Island Institute in anticipation of EPA’s 2015 proposed rulemaking to update rules governing dispersant use under the National Contingency Plan.

Courtesy: Riki Ott, 2015. Tabling in Chicago at a conference.

2015

In response to EPA’s proposed rulemaking on dispersant use (in January), ALERT launched a national “#What’sThePlanEPA? Tour” that led to an outpouring of “unique” public comments—all opposing use and supporting ALERT’s comments.

ALERT’s workshop in Vancouver, British Columbia, prepared citizens to respond to Canada’s proposed rulemaking, announced a couple months after the Marathassa oil spill, to allow Corexit dispersants for use in maritime oil spills.

2015

Following the Marathassa oil spill in English Bay (British Columbia, Canada), ALERT was invited to lead an extended workshop on human health impacts from oil spills and building local capacity to better prepare Vancouver and other communities around English Bay for oil disasters.

Courtesy: Riki Ott, 2015. Ott was also asked to prepare expert witness testimony on human health harm from oil disasters for ally-intervenors seeking to block the proposed Trans Mountain Pipeline tar sands extension project. After 12 years of delay and $25 billion, the pipeline started operations in May 2024.

2016

In response to requests from Gulf Coast communities to “help us understand what these daily chemical exposures do to us,” ALERT launched a “Toxic Trespass Tour” that led to a collaboration effort on developing the Toxic Trespass Training Manual and Health Advocacy Guide, accessible science educational tools about toxic exposure and chemical illness.

2016

In response to requests from citizens harmed by 2014 BP Whiting refinery tar sands oil spill into Lake Michigan and chronic pollution from Whiting refinery wastewater treatment facility, and by the 2010 Enbridge tar sands oil spill, ALERT guided efforts to demand maximum fines and establishment of regional citizens’ advisory councils (as intended by the Oil Pollution Act) as part of federal spill settlements. These documents are templates for future oil spill settlements.

Courtesy: Riki Ott, 2017. Two million people from Pacific Rim nations volunteered to help clean up the Hebei Spirit oil spill.

Courtesy: Riki Ott 2017. On the 10-year memorial, Ott attended the opening of a museum in Taean, South Korea, to honor these volunteers. Ott also spoke about long-term harm to people, communities, and wildlife at the international scientific symposium of Hebei Spirit oil spill along scientists from Spain (Prestige oil spill) and South Korea. These findings preceded similar scientific findings from the BP oil disaster.

2017

An ALERT workshop at the National Tribal Emergency Management Council’s conference on the inadequacies of oil spill response plans to protect Tribal responders, members and substance resources, led to ongoing work with Tribes to address these issues.

ALERT v. EPA

Ott announced ALERT’s lawsuit during the Sundance Film Festival’s premiere screenings ofThe Cost of Silence, a searing investigative documentary about the long-term human health impacts of the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil disaster.

2020

After eight years of delay in finalizing the rulemaking (counting from when the petition was filed in 2012), ALERT and allies sued EPA.

2021

ALERT secured a victory when the court ruled that the 8-year delay was unreasonable and that EPA must update its rules governing dispersant use by May 2023 under court-supervision.

2022

The manufacturer of Corexit dispersants “voluntarily” discontinues its products rather than having to truthfully report the now proven human health impacts of its products.

2023

EPA final rules governing dispersant use will eliminate the more toxic products and include a truth-in-reporting rule to remove a product if the manufacturer provides information that is misleading, inaccurate, or outdated concerning human health impacts.

2023 - 2024

Regional Response Team 10 (RRT 10) and the Northwest Area Committee (NWAC)

Ott co-chaired the 2023 Health and Safety Task Force, chartered by RRT 10 and NWAC. The Task Force recommended that a Worker Health Unit and a Public Health Unit be developed and implemented in the Incident Command Structure for all-hazard disasters. Further, it recommended changes to the federal Occupational Safety and Health Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER) regulations and the Washington state HAZWOPER regulations to strengthen health protection for all-hazard emergency responders.

2024 Petition

ALERT and allies petition the EPA to remove two chemical dispersants, Corexit 9527A and 9500A that were used after the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil disaster, from the list of products authorized for use during oil spill response, based on now proven human health impacts—effective immediately. ALERT also launched the #ExitCorexit Campaign to support this first test of the truth-in-reporting rule.

2024 United Nations

ALERT and allies request United Nations’ bodies that develop, implement, and use its global hazard communication procedures to ban use of Corexit dispersants globally and adopt procedures like in the United States to assure global hazard communications contain accurate and updated information.